Our Health Library information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Please be advised that this information is made available to assist our patients to learn more about their health. Our providers may not see and/or treat all topics found herein.

Topic Contents

- General Information About Urethral Cancer

- Cellular Classification of Urethral Cancer

- Stage Information for Urethral Cancer

- Treatment Option Overview for Urethral Cancer

- Treatment of Distal Urethral Cancer

- Treatment of Proximal Urethral Cancer

- Treatment of Urethral Cancer Associated With Invasive Bladder Cancer

- Treatment of Metastatic or Recurrent Urethral Cancer

- Latest Updates to This Summary (07 / 19 / 2024)

- About This PDQ Summary

Urethral Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

General Information About Urethral Cancer

Incidence and Mortality

Urethral cancer is rare. The annual incidence rate for urethral cancer in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database from 1973 to 2002 in the United States was 4.3 per million for men and 1.5 per million for women, with downward trends over the three decades.[1] The incidence was twice as high in African American individuals as in White individuals (5 per million vs. 2.5 per million). Urethral cancers appear to be associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, particularly HPV16, a strain known to cause cervical cancer.[2,3]

Because urethral cancer is rare, nearly all information about its treatment and the outcomes of therapy is derived from retrospective, single-center case series, which represents a very low Level of evidence C3. Most information comes from cases accumulated over many decades at major academic centers.

Anatomy

The female urethra is largely contained within the anterior vaginal wall. In adults, it is about 4 cm in length.

The male urethra, which averages about 20 cm in length, is divided into distal and proximal portions. The distal urethra, which extends from the tip of the penis to just before the prostate, includes the meatus, the fossa navicularis, the penile or pendulous urethra, and the bulbar urethra. The proximal urethra, which extends from the bulbar urethra to the bladder neck, includes the membranous urethra and the prostatic urethra.

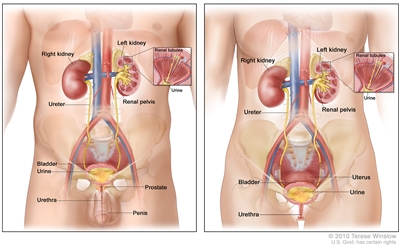

Anatomy of the male urinary system (left panel) and female urinary system (right panel) showing the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The inside of the left kidney shows the renal pelvis. An inset shows the renal tubules and urine. Also shown are the prostate and penis (left panel) and the uterus (right panel). Urine is made in the renal tubules and collects in the renal pelvis of each kidney. The urine flows from the kidneys through the ureters to the bladder. The urine is stored in the bladder until it leaves the body through the urethra.

Prognosis

The prognosis of urethral cancer depends on the following factors:[4,5,6]

- Anatomical location.

- Size.

- Stage.

- Depth of invasion.

Superficial tumors in the distal urethra in both women and men are generally curable. However, deeply invasive lesions are rarely curable by any combination of therapies. In men, the prognosis of tumors in the distal (pendulous) urethra is better than for tumors of the proximal (bulbomembranous) and prostatic urethra, which tend to present at more advanced stages.[7,8] Likewise, distal urethral tumors tend to occur at earlier stages in women and to have a better prognosis than proximal tumors.[9]

References:

- Swartz MA, Porter MP, Lin DW, et al.: Incidence of primary urethral carcinoma in the United States. Urology 68 (6): 1164-8, 2006.

- Wiener JS, Liu ET, Walther PJ: Oncogenic human papillomavirus type 16 is associated with squamous cell cancer of the male urethra. Cancer Res 52 (18): 5018-23, 1992.

- Wiener JS, Walther PJ: A high association of oncogenic human papillomaviruses with carcinomas of the female urethra: polymerase chain reaction-based analysis of multiple histological types. J Urol 151 (1): 49-53, 1994.

- Urethra. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp. 767–76.

- Rabbani F: Prognostic factors in male urethral cancer. Cancer 117 (11): 2426-34, 2011.

- Dalbagni G, Zhang ZF, Lacombe L, et al.: Female urethral carcinoma: an analysis of treatment outcome and a plea for a standardized management strategy. Br J Urol 82 (6): 835-41, 1998.

- Dinney CP, Johnson DE, Swanson DA, et al.: Therapy and prognosis for male anterior urethral carcinoma: an update. Urology 43 (4): 506-14, 1994.

- Dalbagni G, Zhang ZF, Lacombe L, et al.: Male urethral carcinoma: analysis of treatment outcome. Urology 53 (6): 1126-32, 1999.

- Gheiler EL, Tefilli MV, Tiguert R, et al.: Management of primary urethral cancer. Urology 52 (3): 487-93, 1998.

Cellular Classification of Urethral Cancer

In an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program data from 1973 to 2002, the most common histological types of urethral cancer were the following:[1]

- Transitional cell (55%).

- Squamous cell (21.5%).

- Adenocarcinoma (16.4%).

Other cell types, such as melanoma, were extremely rare.[1]

The female urethra is lined by transitional cell mucosa proximally and stratified squamous cells distally. Therefore, transitional cell carcinoma is most common in the proximal urethra, and squamous cell carcinoma predominates in the distal urethra. Adenocarcinoma may occur in both locations and arises from metaplasia of the numerous periurethral glands.

The male urethra is lined by transitional cells in its prostatic and membranous portion and stratified columnar epithelium to stratified squamous epithelium in the bulbous and penile portions. The submucosa of the urethra contains numerous glands. Therefore, urethral cancer in men can manifest the histological characteristics of transitional cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or adenocarcinoma.

Except for the prostatic urethra, where transitional cell carcinoma is most common, squamous cell carcinoma is the predominant histology of urethral neoplasms. Because transitional cell carcinoma of the prostatic urethra may be associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder and/or transitional cell carcinoma arising in prostatic ducts, it is often treated similarly to these primaries and should be separated from the more distal carcinomas of the urethra.

References:

- Swartz MA, Porter MP, Lin DW, et al.: Incidence of primary urethral carcinoma in the United States. Urology 68 (6): 1164-8, 2006.

Stage Information for Urethral Cancer

Prognosis and treatment decisions are determined by the following:[1]

- The anatomical location of the primary tumor.

- The size of the tumor.

- The stage of the cancer.

- The depth of invasion of the tumor.

The histology of the primary tumor is of less importance in estimating response to therapy and survival.[2] Endoscopic examination, urethrography, and magnetic resonance imaging are useful in determining the local extent of the tumor.[3,4]

Distal Urethral Cancer

These lesions are often superficial.

- Female: Lesions of the distal third of the urethra.

- Male: Anterior, or penile, portion of the urethra, including the meatus and pendulous urethra.

Proximal Urethral Cancer

These lesions are often deeply invasive.

- Female: Lesions not clearly limited to the distal third of the urethra.

- Male: Bulbomembranous and prostatic urethra.

Urethral Cancer Associated With Invasive Bladder Cancer

Approximately 5% to 10% of men with cystectomy for bladder cancer may have or may develop urethral cancer distal to the urogenital diaphragm.[5,6]

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Stage Groupings and TNM Definitions

The AJCC has designated staging by TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) classification to define urethral cancer.[1]

Male penile urethra and female urethra

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | ||

| a Reprinted with permission from AJCC: Urethra. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.:AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 767–76. | ||

| 0is | Tis, N0, M0 | Tis = Carcinomain situ. |

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||

| 0a | Ta, N0, M0 | Ta = Noninvasive papillary carcinoma. |

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | ||

| a Reprinted with permission from AJCC: Urethra. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.:AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 767–76. | ||

| I | T1, N0, M0 | T1 = Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue. |

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | ||

| a Reprinted with permission from AJCC: Urethra. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.:AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 767–76. | ||

| II | T2, N0, M0 | T2 = Tumor invades any of the following: corpus spongiosum, periurethral muscle. |

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | ||

| a Reprinted with permission from AJCC: Urethra. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.:AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 767–76. | ||

| III | T1, N1, M0 | T1 = Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue. |

| N1 = Single regional lymph node metastasis in the inguinal region or true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal [hypogastric] and external iliac), or presacral lymph node. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||

| T2, N1, M0 | T2 = Tumor invades any of the following: corpus spongiosum, periurethral muscle. | |

| N1 = Single regional lymph node metastasis in the inguinal region or true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal [hypogastric] and external iliac), or presacral lymph node. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||

| T3, N0, M0 | T3 = Tumor invades any of the following: corpus cavernosum, anterior vagina. | |

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||

| T3, N1, M0 | T3 = Tumor invades any of the following: corpus cavernosum, anterior vagina. | |

| N1 = Single regional lymph node metastasis in the inguinal region or true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal [hypogastric] and external iliac), or presacral lymph node. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | ||

| a Reprinted with permission from AJCC: Urethra. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.:AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 767–76. | ||

| IV | T4, N0, M0 | T4 = Tumor invades other adjacent organs (e.g., invasion of the bladder wall). |

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||

| T4, N1, M0 | T4 = Tumor invades other adjacent organs (e.g., invasion of the bladder wall). | |

| N1 = Single regional lymph node metastasis in the inguinal region or true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal [hypogastric] and external iliac), or presacral lymph node. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||

| Any T, N2, M0 | TX = Primary tumor cannot be assessed. | |

| T0 = No evidence of primary tumor. | ||

| Ta = Noninvasive papillary carcinoma. | ||

| Tis = Carcinomain situ. | ||

| T1 = Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue. | ||

| T2 = Tumor invades any of the following: corpus spongiosum, periurethral muscle. | ||

| T3 = Tumor invades any of the following: corpus cavernosum, anterior vagina. | ||

| T4 = Tumor invades other adjacent organs (e.g., invasion of the bladder wall). | ||

| N2 = Multiple regional lymph node metastasis in the inguinal region or true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal [hypogastric] and external iliac), or presacral lymph node. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||

| Any T, Any N, M1 | Any T = See descriptions above in this table, stage IV, Any T, N2, M0. | |

| NX = Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||

| N1 = Single regional lymph node metastasis in the inguinal region or true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal [hypogastric] and external iliac), or presacral lymph node. | ||

| N2 = Multiple regional lymph node metastasis in the inguinal region or true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal [hypogastric] and external iliac), or presacral lymph node. | ||

| M1 = Distant metastasis. | ||

References:

- Urethra. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp. 767–76.

- Grigsby PW, Corn BW: Localized urethral tumors in women: indications for conservative versus exenterative therapies. J Urol 147 (6): 1516-20, 1992.

- Ryu J, Kim B: MR imaging of the male and female urethra. Radiographics 21 (5): 1169-85, 2001 Sep-Oct.

- Pavlica P, Barozzi L, Menchi I: Imaging of male urethra. Eur Radiol 13 (7): 1583-96, 2003.

- Mark JR, Hurwitz M, Gomella LG: Cancer of the urethra and penis. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1136-44.

- Erckert M, Stenzl A, Falk M, et al.: Incidence of urethral tumor involvement in 910 men with bladder cancer. World J Urol 14 (1): 3-8, 1996.

Treatment Option Overview for Urethral Cancer

Information about the treatment of urethral cancer and the outcomes of therapy is derived from retrospective, single-center case series and represents a very low Level of evidence C3. Most of this information comes from the small numbers of cases accumulated over many decades at major academic centers. Therefore, the treatment in these reports is usually not standardized and spans eras of shifting supportive care practices. Because urethral cancer is rare, its treatment may also reflect extrapolation from the management of other urothelial malignancies, such as bladder cancer in the case of transitional cancers and anal cancer in the case of squamous cell carcinomas.

Surgery

Surgery is the mainstay of therapy for urethral cancers in both women and men.[Level of evidence C3] The surgical approach depends on tumor stage and anatomic location, and tumor grade plays a less important role in treatment decisions.[1,2] Although the traditional recommendation has been to achieve a 2-cm tumor-free margin, the optimal surgical margin has not been rigorously studied and is not well defined. The role of lymph node dissection is not clear in the absence of clinical involvement, and the role of prophylactic dissection is controversial.[2] Radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy may be added in some cases in patients with extensive disease or in an attempt at organ preservation. However, there are no clear guidelines for patient selection, and the low level of evidence precludes confident conclusions about their incremental benefit.[2,3]

Ablative techniques, such as transurethral resection, electroresection and fulguration, or laser vaporization-coagulation, are used to preserve organ function in cases of superficial anterior tumors, although the supporting literature is scant.[2]

Radiation Therapy

External-beam radiation therapy, brachytherapy, or a combination is sometimes used as the primary therapy for early-stage proximal urethral cancers, particularly in women.[Level of evidence C3] Brachytherapy may be delivered with low-dose-rate iridium Ir 192 sources using a template or urethral catheter. Definitive radiation is also sometimes used for advanced-stage tumors, but because monotherapy of large tumors has shown poor tumor control, it is more frequently incorporated into combined modality therapy after surgery or with chemotherapy.[4] There are no head-to-head comparisons of these various approaches, and patient selection may explain differences in outcomes among the regimens.[Level of evidence C3]

The most commonly used tumor doses are in the range of 60 Gy to 70 Gy. Severe complication rates for definitive radiation therapy are about 16% to 20% and include fistula development, especially for large tumors invading the vagina, bladder, or rectum. Urethral strictures also occur in the setting of urethral-sparing treatment. Toxicity rates increase at doses greater than 65 Gy to 70 Gy. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy has become more common in an attempt to decrease local morbidity of the radiation.[4]

Chemotherapy

The literature on chemotherapy for urethral carcinoma is anecdotal in nature and restricted to retrospective, single-center case series or case reports.[5][Level of evidence C3] A wide variety of agents used alone or in combination have been reported over the years, and their use has largely been extrapolated from experience with other urinary tract tumors.

For squamous cell cancers, agents that have been used in penile cancer or anal carcinoma include the following:[3,5]

- Cisplatin.

- Fluorouracil.

- Bleomycin.

- Methotrexate.

- Irinotecan.

- Gemcitabine.

- Paclitaxel.

- Docetaxel.

- Mitomycin.

Chemotherapy for transitional cell urethral tumors is extrapolated from experience with transitional cell bladder tumors and, therefore, usually contains the following:[1,4,5,6,7]

- Methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin.

- Paclitaxel.

- Carboplatin.

- Ifosfamide, with occasional complete responses.

Chemotherapy has been used alone for metastatic disease or in combination with radiation therapy and/or surgery for locally advanced urethral cancer. It may be used in the neoadjuvant setting with radiation therapy in an attempt to increase the resectability rate or to preserve organs.[3] However, the impact of any of these regimens on survival is not known for any stage or setting.

Fluorouracil dosing

The DPYD gene encodes an enzyme that catabolizes pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines, like capecitabine and fluorouracil. An estimated 1% to 2% of the population has germline pathogenic variants in DPYD, which lead to reduced DPD protein function and an accumulation of pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines in the body.[8,9] Patients with the DPYD*2A variant who receive fluoropyrimidines may experience severe, life-threatening toxicities that are sometimes fatal. Many other DPYD variants have been identified, with a range of clinical effects.[8,9,10] Fluoropyrimidine avoidance or a dose reduction of 50% may be recommended based on the patient's DPYD genotype and number of functioning DPYD alleles.[11,12,13]DPYD genetic testing costs less than $200, but insurance coverage varies due to a lack of national guidelines.[14] In addition, testing may delay therapy by 2 weeks, which would not be advisable in urgent situations. This controversial issue requires further evaluation.[15]

References:

- Mark JR, Hurwitz M, Gomella LG: Cancer of the urethra and penis. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1136-44.

- Karnes RJ, Breau RH, Lightner DJ: Surgery for urethral cancer. Urol Clin North Am 37 (3): 445-57, 2010.

- Cohen MS, Triaca V, Billmeyer B, et al.: Coordinated chemoradiation therapy with genital preservation for the treatment of primary invasive carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol 179 (2): 536-41; discussion 541, 2008.

- Koontz BF, Lee WR: Carcinoma of the urethra: radiation oncology. Urol Clin North Am 37 (3): 459-66, 2010.

- Trabulsi EJ, Hoffman-Censits J: Chemotherapy for penile and urethral carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am 37 (3): 467-74, 2010.

- VanderMolen LA, Sheehy PF, Dillman RO: Successful treatment of transitional cell carcinoma of the urethra with chemotherapy. Cancer Invest 20 (2): 206-7, 2002.

- Lin CC, Hsu CH, Huang CY, et al.: Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel, cisplatin plus infusional high dose 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic urothelial carcinoma. J Urol 177 (1): 84-9; discussion 89, 2007.

- Sharma BB, Rai K, Blunt H, et al.: Pathogenic DPYD Variants and Treatment-Related Mortality in Patients Receiving Fluoropyrimidine Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 26 (12): 1008-1016, 2021.

- Lam SW, Guchelaar HJ, Boven E: The role of pharmacogenetics in capecitabine efficacy and toxicity. Cancer Treat Rev 50: 9-22, 2016.

- Shakeel F, Fang F, Kwon JW, et al.: Patients carrying DPYD variant alleles have increased risk of severe toxicity and related treatment modifications during fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics 22 (3): 145-155, 2021.

- Amstutz U, Henricks LM, Offer SM, et al.: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase Genotype and Fluoropyrimidine Dosing: 2017 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 103 (2): 210-216, 2018.

- Henricks LM, Lunenburg CATC, de Man FM, et al.: DPYD genotype-guided dose individualisation of fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with cancer: a prospective safety analysis. Lancet Oncol 19 (11): 1459-1467, 2018.

- Lau-Min KS, Varughese LA, Nelson MN, et al.: Preemptive pharmacogenetic testing to guide chemotherapy dosing in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: a qualitative study of barriers to implementation. BMC Cancer 22 (1): 47, 2022.

- Brooks GA, Tapp S, Daly AT, et al.: Cost-effectiveness of DPYD Genotyping Prior to Fluoropyrimidine-based Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Colon Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 21 (3): e189-e195, 2022.

- Baker SD, Bates SE, Brooks GA, et al.: DPYD Testing: Time to Put Patient Safety First. J Clin Oncol 41 (15): 2701-2705, 2023.

Treatment of Distal Urethral Cancer

Treatment Options for Female Distal Urethral Cancer

If the malignancy is at or just within the meatus and superficial parameters (stage 0/Tis, Ta), open excision or electroresection and fulguration may be possible. Tumor destruction using neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) or CO2 laser vaporization-coagulation represents an alternative option. For large lesions (T1) and more invasive lesions (T2), brachytherapy or a combination of brachytherapy and external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) are alternatives to surgical resection of the distal third of the urethra. Patients with T3 distal urethral lesions or lesions that recur after treatment with local excision or radiation therapy require anterior exenteration and urinary diversion.

If inguinal lymph nodes are palpable, frozen section confirmation of a tumor should be obtained. If positive for malignancy, ipsilateral lymph node dissection is indicated. If no inguinal adenopathy exists, lymph node dissection is not generally performed, and the nodes are monitored clinically.

Treatment options for female distal urethral cancer include the following:

- Open excision and organ-sparing conservative surgical therapy.[1]

- Ablative techniques, such as transurethral resection, electroresection and fulguration, or laser vaporization-coagulation (Tis, Ta, T1 lesions).[2,3]

- EBRT, brachytherapy, or a combination of the two (T1, T2 lesions).[4]

- Anterior exenteration with or without preoperative radiation and diversion (T3 lesions or recurrent lesions).[2,3]

The level of evidence for these treatment options is Level of evidence C3.

Treatment Options for Male Distal Urethral Cancer

If the malignancy is in the pendulous urethra and is superficial, there is potential for long-term disease-free survival. In the rare cases that involve mucosa only (Tis, Ta), resection and fulguration may be used. For infiltrating lesions in the fossa navicularis, amputation of the glans penis may be adequate treatment. For lesions involving more proximal portions of the distal urethra, excision of the involved segment of the urethra, preserving the penile corpora, may be feasible for superficial tumors. Penile amputation is used for infiltrating lesions. Traditionally, a 2-cm margin proximal to the tumor is used, but the optimal margin has not been well studied. Local recurrences after amputation are rare.

The role of radiation therapy in the treatment of anterior urethral carcinoma in men is not well defined. Some anterior urethral cancers have been cured with radiation alone or a combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy.[4,5]

If inguinal lymph nodes are palpable, ipsilateral node dissection is indicated after frozen section confirmation of a tumor because a cure is still achievable with limited regional nodal metastases. If no inguinal adenopathy exists, lymph node dissection is not generally performed, and the nodes are monitored clinically.

Treatment options for male distal urethral cancer include the following:

- Open-excision and organ-sparing conservative surgery.[1,3]

- Ablative techniques, such as transurethral resection, electroresection and fulguration, or laser vaporization-coagulation (Tis, Ta, T1 lesions).[2,3]

- Amputation of the penis (T1, T2, T3 lesions).

- Radiation (T1, T2, T3 lesions, if amputation is refused).[4]

- Combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy.[5]

The level of evidence for these treatment options is Level of evidence C3.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Davis JW, Schellhammer PF, Schlossberg SM: Conservative surgical therapy for penile and urethral carcinoma. Urology 53 (2): 386-92, 1999.

- Mark JR, Hurwitz M, Gomella LG: Cancer of the urethra and penis. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1136-44.

- Karnes RJ, Breau RH, Lightner DJ: Surgery for urethral cancer. Urol Clin North Am 37 (3): 445-57, 2010.

- Koontz BF, Lee WR: Carcinoma of the urethra: radiation oncology. Urol Clin North Am 37 (3): 459-66, 2010.

- Cohen MS, Triaca V, Billmeyer B, et al.: Coordinated chemoradiation therapy with genital preservation for the treatment of primary invasive carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol 179 (2): 536-41; discussion 541, 2008.

Treatment of Proximal Urethral Cancer

Treatment Options for Female Proximal Urethral Cancer

Lesions of the proximal urethra or the entire length of the urethra are usually associated with invasion and a high incidence of pelvic nodal metastases. The prospects for cure are limited except in the case of small tumors. The best results have been achieved with exenterative surgery and urinary diversion, with 5-year survival rates ranging from 10% to 20%.

In an effort to shrink tumor margins, increase the resectability rate of gross tumor, and decrease local recurrence, adjunctive preoperative radiation therapy is a reasonable option. Pelvic lymphadenectomy is performed concomitantly. Ipsilateral inguinal lymph node dissection is indicated only if biopsy specimens of ipsilateral palpable adenopathy are positive on a frozen section. For tumors that do not exceed 2 cm in greatest dimension, radiation alone, nonexenterative surgery alone, or a combination of the two may be sufficient to provide an excellent outcome.

It is reasonable to consider removal of part of the pubic symphysis and the inferior pubic rami to maximize the surgical margin and reduce local recurrence. The perineal closure and vaginal reconstruction can be accomplished with the use of myocutaneous flaps.

The prognosis of female urethral cancer is related to the size of the lesion at presentation. For lesions smaller than 2 cm in diameter, a 5-year survival rate of 60% can be anticipated. For lesions larger than 4 cm in diameter, the 5-year survival rate falls to 13%.

Treatment options for female proximal urethral cancer include the following:

- Preoperative radiation followed by anterior exenteration and urinary diversion with bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection, with or without inguinal lymph node dissection.[1]

- For tumors that do not exceed 2 cm in greatest dimension, radiation alone, nonexenterative surgery alone, or a combination of the two may be sufficient to provide an excellent outcome.[1,2]

The level of evidence for these treatment options is Level of evidence C3.

Treatment Options for Male Proximal Urethral Cancer

Lesions of the bulbomembranous urethra require radical cystoprostatectomy and en bloc penectomy to achieve adequate margins of resection, minimize local recurrence, and achieve long-term, disease-free survival. Pelvic lymphadenectomy is also performed because of the high incidence of positive lymph nodes and the limited added morbidity.

Despite extensive surgery, local recurrence is common, and this event is invariably associated with eventual death from the disease. Five-year survival rates are only 15% to 20%. In an effort to shrink tumor margins, the use of preoperative adjunctive radiation therapy may be considered. In an effort to increase the surgical margins of dissection, resection of the inferior pubic rami and the lower portion of the pubic symphysis has been used. Urinary diversion is required.[3]

Ipsilateral inguinal lymph node dissection is indicated if palpable ipsilateral inguinal adenopathy is found on physical examination and confirmed to be neoplasm by frozen section.

Treatment options for male proximal urethral cancer include the following:

- Preoperative radiation or combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy followed by cystoprostatectomy, urinary diversion, and penectomy with bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection, with or without inguinal lymph node dissection.[4]

The level of evidence for these treatment options is Level of evidence C3.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Koontz BF, Lee WR: Carcinoma of the urethra: radiation oncology. Urol Clin North Am 37 (3): 459-66, 2010.

- Grigsby PW, Corn BW: Localized urethral tumors in women: indications for conservative versus exenterative therapies. J Urol 147 (6): 1516-20, 1992.

- Su LM, Smith JA Jr.: Laparoscopic and robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al.: Campbell-Walsh Urology. 10th ed. Elsevier Saunders, 2012, pp 2830-2849.

- Karnes RJ, Breau RH, Lightner DJ: Surgery for urethral cancer. Urol Clin North Am 37 (3): 445-57, 2010.

Treatment of Urethral Cancer Associated With Invasive Bladder Cancer

Approximately 10% (range, 4%–17%) of patients who undergo cystectomy for bladder cancer can be expected to have or to later develop clinical neoplasm of the urethra distal to the urogenital diaphragm. Factors associated with the risk of urethral recurrence after cystectomy include the following:[1,2]

- Tumor multiplicity.

- Papillary pattern.

- Carcinoma in situ.

- Tumor location at the bladder neck.

- Prostatic urethral mucosal or stromal involvement.

The benefits of urethrectomy at the time of cystectomy need to be weighed against the morbidity factors, which include added operating time, hemorrhage, and the potential for perineal hernia. Tumors found incidentally on pathological examination are much more likely to be superficial or in situ in contrast to those that present with clinical symptoms at a later date, when the likelihood of invasion within the corporal bodies is high. The former lesions are often curable, and the latter are only rarely so. Indications for urethrectomy in continuity with cystoprostatectomy are the following:

- Visible tumor in the urethra.

- Positive swab cytology of the urethra.

- Positive margins of the membranous urethra on frozen section taken at the time of cystoprostatectomy.

- Multiple in situ bladder tumors that extend onto the bladder neck and proximal prostatic urethra.

If the urethra is not removed at the time of cystectomy, follow-up includes periodic cytologic evaluation of saline urethral washings.[2]

Treatment options for urethral cancer associated with invasive bladder cancer include the following:

- In continuity cystourethrectomy.

- Monitor urethral cytology and delayed urethrectomy, if necessary.

The level of evidence for these treatment options is Level of evidence C3.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Mark JR, Hurwitz M, Gomella LG: Cancer of the urethra and penis. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1136-44.

- Sherwood JB, Sagalowsky AI: The diagnosis and treatment of urethral recurrence after radical cystectomy. Urol Oncol 24 (4): 356-61, 2006 Jul-Aug.

Treatment of Metastatic or Recurrent Urethral Cancer

Local recurrences of urethral cancer may be amenable to local modality therapy with radiation or surgery, with or without chemotherapy. For more information, see the Treatment Option Overview for Urethral Cancer section. Metastatic disease may be treated with regimens in common use for other urothelial transitional cell or squamous cell carcinomas, or anal carcinomas, depending on the histology.[1,2,3]

Treatment options for metastatic or recurrent urethral cancer include the following:

- Surgical excision of locally recurrent urethral cancer after radiation therapy should be considered, if feasible.

- Combination radiation therapy and wider surgical resection should be considered for locally recurrent urethral cancer after surgery alone.

- Clinical trials using chemotherapy should be considered for metastatic urethral cancer. Transitional cell cancer of the urethra may respond favorably to the same chemotherapy regimens used for advanced transitional cell cancer of the bladder.[1,2,3,4]

The level of evidence for these treatment options is Level of evidence C3.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Mark JR, Hurwitz M, Gomella LG: Cancer of the urethra and penis. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1136-44.

- Trabulsi EJ, Hoffman-Censits J: Chemotherapy for penile and urethral carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am 37 (3): 467-74, 2010.

- Lin CC, Hsu CH, Huang CY, et al.: Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel, cisplatin plus infusional high dose 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic urothelial carcinoma. J Urol 177 (1): 84-9; discussion 89, 2007.

- VanderMolen LA, Sheehy PF, Dillman RO: Successful treatment of transitional cell carcinoma of the urethra with chemotherapy. Cancer Invest 20 (2): 206-7, 2002.

Latest Updates to This Summary (07 / 19 / 2024)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Treatment Option Overview for Urethral Cancer

Added Fluorouracil dosing as a new subsection.

This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionals pages.

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of urethral cancer. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Urethral Cancer Treatment are:

- Juskaran S. Chadha, DO (Moffitt Cancer Center)

- Jad Chahoud, MD, MPH (Moffitt Cancer Center)

- Timothy Gilligan, MD (Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries.

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Urethral Cancer Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/urethral/hp/urethral-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389356]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either "standard" or "under clinical evaluation." These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website's Email Us.

Last Revised: 2024-07-19

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Learn how we develop our content.

Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.